Galton–Watson process

The Galton–Watson process is a branching stochastic process arising from Francis Galton's statistical investigation of the extinction of family names. The process models family names as patrilineal (passed from father to son), while offspring are randomly either male or female, and names become extinct if the family name line dies out (holders of the family name die without male descendants). While this is an accurate description of Y chromosome transmission in genetics, and the model is thus useful for understanding human Y-chromosome DNA haplogroups – and is also of use in understanding other processes (as described below) – its application to actual extinction of family names is fraught. In practice family names change for many other reasons, and dying out of name line is only one factor, as discussed in examples, below; the Galton–Watson process is thus of limited applicability in understanding actual family name distributions.

There was concern amongst the Victorians that aristocratic surnames were becoming extinct. Galton originally posed the question regarding the probability of such an event in the Educational Times of 1873, and the Reverend Henry William Watson replied with a solution. Together, they then wrote an 1874 paper entitled On the probability of extinction of families. Galton and Watson appear to have derived their process independently of the earlier work by I. J. Bienaymé; see Heyde and Seneta 1977. For a detailed history see Kendall (1966 and 1975).

Contents |

Concepts

Assume, as was taken for granted in Galton's time, that surnames are passed on to all male children by their father. Suppose the number of a man's sons to be a random variable distributed on the set { 0, 1, 2, 3, ... }. Further suppose the numbers of different men's sons to be independent random variables, all having the same distribution.

Then the simplest substantial mathematical conclusion is that if the average number of a man's sons is 1 or less, then their surname will almost surely die out, and if it is more than 1, then there is more than zero probability that it will survive for any given number of generations.

Modern applications include the survival probabilities for a new mutant gene, or the initiation of a nuclear chain reaction, or the dynamics of disease outbreaks in their first generations of spread, or the chances of extinction of small population of organisms; as well as explaining (perhaps closest to Galton's original interest) why only a handful of males in the deep past of humanity now have any surviving male-line descendants, reflected in a rather small number of distinctive human Y-chromosome DNA haplogroups.

A corollary of high extinction probabilities is that if a lineage has survived, it is likely to have experienced, purely by chance, an unusually high growth rate in its early generations at least when compared to the rest of the population.

Mathematical definition

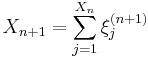

A Galton–Watson process is a stochastic process {Xn} which evolves according to the recurrence formula X0 = 1 and

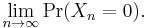

where for each n,  is a sequence of IID natural number-valued random variables. The extinction probability (i.e. the probability of final extinction) is given by

is a sequence of IID natural number-valued random variables. The extinction probability (i.e. the probability of final extinction) is given by

This is clearly equal to zero if each member of the population has exactly one descendent. Excluding this case (usually called the trivial case) there exists a simple necessary and sufficient condition, which is given in the next section.

Extinction criterion for Galton–Watson process

In the non-trivial case the probability of final extinction is equal to one if E{ξ1} ≤ 1 and strictly less than one if E{ξ1} > 1.

The process can be treated analytically using the method of probability generating functions.

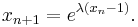

If the number of children ξ j at each node follows a Poisson distribution, a particularly simple recurrence can be found for the total extinction probability xn for a process starting with a single individual at time n = 0:

giving the curves plotted above.

Bisexual Galton–Watson process

In the classical Galton–Watson process described above, only men are considered, effectively modeling reproduction as asexual. A model more closely following actual sexual reproduction is the so-called 'bisexual Galton–Watson process', where only couples reproduce. (Bisexual in this context refers to the number of sexes involved, not sexual orientation.) In this process, each child is supposed as male or female, independently of each other, with a specified probability, and a so-called 'mating function' determines how many couples will form in a given generation. As before, reproduction of different couples are considered to be independent of each other. Now the analogue of the trivial case corresponds to the case of each male and female reproducing in exactly one couple, having one male and one female descendent, and that the mating function takes the value of the minimum of the number of males and females (which are then the same from the next generation onwards).

Since the total reproduction within a generation depends now strongly on the mating function, there exists in general no simple necessary and sufficient condition for final extinction as it is the case in the classical Galton–Watson process. However, excluding the non-trivial case, the concept of the averaged reproduction mean (Bruss (1984)) allows for a general sufficient condition for final extinction, treated in the next section.

Extinction criterion (bisexual Galton–Watson process)

If in the non-trivial case the averaged reproduction mean per couple stays bounded over all generations and will not exceed 1 for a sufficiently large population size, then the probability of final extinction is always 1.

Examples

Citing historical examples of Galton–Watson process is complicated due to the history of family names often deviating significantly from the theoretical model. Notably, new names can be created, existing names can be changed over a person's lifetime, and people historically have often assumed names of unrelated persons, particularly nobility. Thus, a small number of family names at present is not in itself evidence for names having become extinct over time, or that they did so due to dying out of family name lines – that requires that there were more names in the past and that they die out due to the line dying out, rather than the name changing for other reasons, such as vassals assuming the name of their lord.

Chinese names are a well-studied example of surname extinction: there are currently only about 3,100 surnames in use in China, compared with close to 12,000 recorded in the past,[1][2] with 22% of the population sharing three family names (numbering close to 300 million people), and the top 200 names covering 96% of the population. Names have changed or become extinct for various reasons such as people taking the names of their rulers, orthographic simplifications, taboos against using characters from an emperor's name, among others.[2] While family name lines dying out may be a factor in the surname extinction, it is by no means the only or even a significant factor. Indeed, the most significant factor affecting the surname frequency is other ethnic groups identifying as Han and adopting Han names.[2] Further, while new names have arisen for various reasons, this has been outweighed by old names disappearing.[2]

By contrast, some nations have adopted family names only recently. This means both that they have not experienced surname extinction for an extended period, and that the names were adopted when the nation had a relatively large population, rather than the smaller populations of ancient times.[2] Further, these names have often been chosen creatively and are very diverse. Examples include:

- Japanese names, which in general use date only to the Meiji restoration in the late 19th century (when the population was over 30,000,000), have over 100,000 family names, surnames are very varied, and the government restricts married couples to using the same surname.

- Many Dutch names have only included a family name since the Napoleonic Wars in the early 19th century, and there are over 68,000 Dutch family names.

- Thai names have only included a family name since 1920, and only a single family can use a given family name, hence there are a great number of Thai names. Further, Thai people change their family names with some frequency, complicating the analysis.

On the other hand, some examples of high concentration of family names is not primarily due to the Galton–Watson process:

- Vietnamese names have about 100 family names, and 60% of the population sharing three family names. The name Nguyễn alone is estimated to be used by almost 40% of the Vietnamese population, and 90% share 15 names. However, as the history of the Nguyễn name makes clear, this is in no small part due to names being forced on people or adopted for reasons unrelated to genetic relation.

- Korean names are similarly concentrated, with 250 family names, and 45% of the population sharing three family names. However, as recently as 1910, over half the population did not have family names.[3] The lack of diversity is thus not primarily due to the Galton–Watson process, but rather to family names, though recent, not being chosen creatively, but rather on the basis of existing names.

See also

References

- ^ "O rare John Smith", The Economist: 32, June 3, 1995, "Only 3,100 surnames are now in use in China [...] compared with nearly 12,000 in the past. An 'evolutionary dwindling' of surnames is common to all societies. [...] [B]ut in China, [Du] says, where surnames have been in use far longer than in most other places, the paucity has become acute."

- ^ a b c d e Du, Ruofu; Yida, Yuan; Hwang, Juliana; Mountain, Joanna L.; Cavalli-Sforza, L. Luca (1992), Chinese Surnames and the Genetic Differences between North and South China, Journal of Chinese Linguistics Monograph Series, pp. 18–22 (History of Chinese surnames and sources of data for the present research), http://hsblogs.stanford.edu/morrison/files/2011/02/27.pdf, also part of Morrison Institute for Population and Resource Studies Working papers

- ^ Daum 백과사전 : 이름

- F. Thomas Bruss (1984). "A Note on Extinction Criteria for Bisexual Galton–Watson Processes". Journal of Applied Probability 21: 915–919.

- C C Heyde and E Seneta (1977). I.J. Bienayme: Statistical Theory Anticipated. Berlin, Germany.

- Kendall, D. G. (1966). "Branching Processes Since 1873". Journal of the London Mathematical Society s1-41: 385–406. doi:10.1112/jlms/s1-41.1.385. ISSN 0024-6107.

- Kendall, D. G. (1975). "The Genealogy of Genealogy Branching Processes before (and after) 1873". Bulletin of the London Mathematical Society 7 (3): 225–253. doi:10.1112/blms/7.3.225. ISSN 0024-6093.

- H W Watson and Francis Galton, "On the Probability of the Extinction of Families", Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain, volume 4, pages 138–144, 1875.